For a small village, Eddleston has quite an interesting history.

The name Edulfstun dates to some time shortly before 1189 when it was granted to Edulf son of Utred, in the reign of William the Lion. But before that, earlier in the twelfth century, it was called Gillemorestun (Gaelic meaning ‘St Mary’s Lad’s toun’). Before that it was called Pentciacob (meaning ‘headland of James’) in the Cumbric language (similar to Ancient Welsh) spoken by the Britons of southern Scotland. This evolution of placenames illustrates the sequence of languages spoken in this part of the Scottish Borders during the early medieval period.

Before the village were three rings. Not of metal but earthworks amongst the surrounding hills – Northshield Rings, Milkieston Rings and Wormiston Rings. These three hillforts derive from the Iron Age. Whether they were contemporary with each other or replaced one after the other, only excavation may tell. There are other buried archaeological remains around Eddleston too, findspots of early prehistoric stone tools and the remains of a souterrain (a semi-subterranean chamber built for storage during the Iron Age).

The oldest house in Eddleston is Moredun, tucked behind the Horsehoe Inn. This was once a tower-house during the sixteenth century, its upper half removed and new windows inserted in the eighteenth century.

The oldest map to depict Eddleston in any detail is Roy’s map of 1752-55, which records ‘Ethelston Kirk’ and a cluster of buildings south of Longcote Burn. Interestingly, the road north from Peebles at that time cut north-west across the Eddleston Water, in the direction of Darnhall Mains Farm, rather than the route of the modern A703 (or the Old Edinburgh Road) which lie to the east of Eddleston Water.

In 1796, the village of ‘Edlestown’ had a population of 180, out of a parish population of 710, according to the local minister Patrick Robertson (in the Statistical Account of Scotland). As well as landowners and farmers, there were ploughmen, labourers, servants, maid-servants, carpenters, masons, tailors and weavers in the parish. While the local farms were mainly concerned with raising sheep and black cattle, barley, hay, oats, pease, potatoes and turnips were also produced. At this time, ‘the culture of turnips and sown grass hay becomes every year more extensive’, according to the local minister, the agricultural improvements of the era evident.

By 1831, the population of the parish had grown to 836, though the population of the village itself had grown only by a little to 190. Of the 144 families in the parish all but 29 were employed in agriculture. Further agricultural improvements had been made by this time, particularly the reclaiming and draining of waste land and the enclosing of fields. The minister of the parish then was Patrick Robertson, son of the previous minister, and fourth of that line to minister Eddeston parish, the first being James Robertson ordained minister of Eddleston in 1697.

It seems from the 1834 account of Patrick Robertson (in the New Statistical Account of Scotland published in 1845), that customs in the parish of ‘Eddlestone’ were changing quite profoundly at this time. Until the middle of the eighteenth century the universal custom was for the farmer and his family to eat with their servants altogether. But by 1834, the line of demarcation between master and servant had been distinctly drawn. ‘A small landed proprietor, who was alive within these fifteen years, was among the last to give it up…at length he consented to take a cup of tea at breakfast with his wife in the parlour, upon condition that he should first have his pint bicker of porridge as usual with his servants in the kitchen.’ Even worse, ‘in several families tea is substituted for porridge and milk at breakfast, and it is to be regretted that this pernicious habit is gradually gaining ground.’ (who knew?!)

The language generally spoken in the parish in 1834 was a ‘corrupt Scotch with a barbarous mixture of English…with only a few of the oldest people able to speak the Scottish dialect in its purity. These, however, are rapidly disappearing, and in a few years more in all probability there will not be one person alive who could have held converse with his grandfather without the aid of a dictionary.’

In those days, a fair was held annually in the village on 25th September. It had formerly been a great cattle-market but by 1834 the only business transacted was the hiring of farm-servants for the winter.

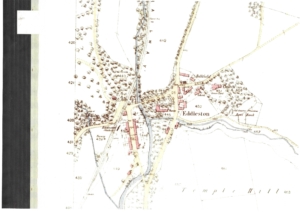

The Ordnance Survey map of 1856 depicts Eddleston in greater detail still than Roy’s map of 1752-55. The core of the village lay just west of the church and north of the Longcote Burn (where it had probably been in Roy’s time too – he just got this wrong!). Many of these buildings are still here – one can recognise the cottage that shortly after became the Horseshoe Inn. Moredun house and its adjacent cottages are apparent too, as is the old school (now the accommodation rooms of the Horseshoe Inn). The main road through the village heading north (along the old Edinburgh Road) is apparent in the 1856 map. What is now missing is the Corn Mill that once lay south of the Longcote Burn (one can still see the remains of the mill lade in the field behind this); two houses now occupy this spot. Also gone is the Manse that once stood on the west side of the Peebles/Edinburgh road; again modern houses occupy this spot.

By 1856, Eddleston had expanded west of its earlier core; the cottages along Station Road are depicted in the map above, as is the Railway Station. The railway line closed in the mid 1900s. It ran through the village where the Station Lye Cul-de Sac now stands. The original station platform remains, and the waiting room and ticket office have been converted into a house. However, many of the original features remain, including the platform clock, which can be seen from the road.

Currently there are approximately 270 residences in and around Eddleston Village and a population of about 550 people.

The Horseshoe Inn

The old smiddy and cottages became the Horseshoe Inn in 1862. Around the Inn, relics from the smiddy are hanging on the wall.

Not that long ago, the present-day restaurant was still the garden for one of the old cottages. The stained-glass window in the restaurant, the impressive frontage to the bar area and many of the doors were saved from the local church.

Not that long ago, the present-day restaurant was still the garden for one of the old cottages. The stained-glass window in the restaurant, the impressive frontage to the bar area and many of the doors were saved from the local church.

The Horseshoe Lodge, in the corner of the car park was originally the old Primary School, being converted in 1998 to ensuite accommodation.

Church and Graveyard

The old graveyard around the Church has headstones dating back to the 18th Century, identifying the local farm owners and other tradesmen such as candle makers and shoemakers. Although the Church was extensively rebuilt around 200 years ago, there has been a church in Eddleston since the 12th Century.

The current church has none of the original fabric, but within it there are relics from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries including an 18th century sundial and 17th and 18th century armorial panels and funerary monuments. More information about this is available from the Peeblesshire Archaeological Society.

The bell, which hangs in the belfry, was cast in 1507. It was thought to have been donated by the Murrays of Black Barony to celebrate their arrival in the village. It is still wrung each Sunday morning before the church service begins.

From Poorhouse to Park

When the Peeblesshire Poorhouse was sold, the Parish Council came into £120. The money was to be used to provide a park for the youth of the community.

However, when Lord Elibank was approached to ask his permission to purchase the ground he said his father, the Viscount, would donate the ground to commemorate the 50th year of his accession to the Estate.

The village knew the Murrays of Blackbarony for their generosity. In 1923 Elibank Park was opened in the most appalling weather conditions.

Do you have an event or news item you want included on the website?